Learn about the Shroud

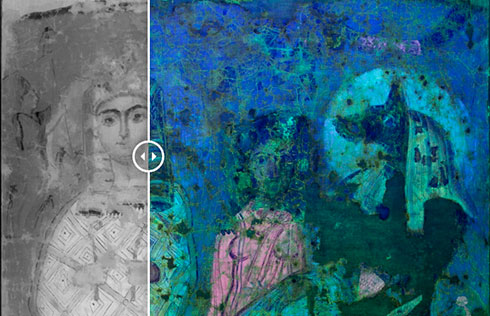

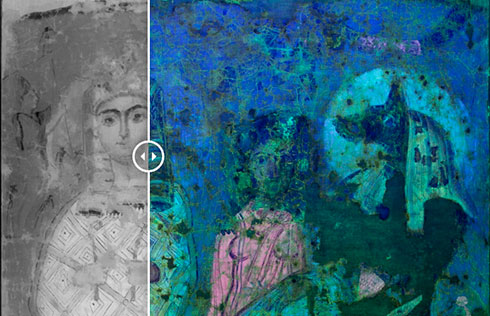

We continue the call for donations for the restoration campaign of the Egyptian funerary shroud of the 2nd century AD with a unique image. A woman in a pink tunic holding a hand of a boy in a white toga is depicted in the center of the shroud. The faces of the woman and the child, who is, without any doubt, her little son, are individually portrayed. It is highly probable that the woman and the child died at the same time and thus are depicted together on this funerary cerement. It is also possible that it was the woman who died, and the artist added the image of a child to emphasize her maternal role. The mother and her son stand between the two Egyptian gods – Anubis (the figure with a jackal’s head), responsible for embalming and Osiris (the mummy-like figure), the ruler of the underworld.

The shroud is in urgent need of conservation. After the transferring to the new canvas, carelessly conducted in the late nineteenth–early twentieth century, numerous fractures and deformations, the loss of canvas, and peeling of paint layers occurred on the shroud with the passage of time. Due to the use of gelatinous glue, the fabric of the shroud degraded and dried up. It is planned to invite the experts from several research institutions, as well as restorers from the Grabar Art Conservation Center (Moscow), the State Hermitage (St. Petersburg), the Louvre (Paris), and the Metropolitan Museum (New York) to contribute to the project. The experience of world’s leading museums will make it possible to develop the most effective methods for the preservation of this unique object.

All those who wish to support the restoration program can donate online.

Historical Background

The burial shroud comes from the collection of the Russian Egyptologist and Orientalist Vladimir Golenishchev (1856–1947), a professional scholar who spent thirty years of his life collecting oriental antiquities, and in 1909 sold his collection to the Museum of Fine Arts. The Collection of Golenishchev contains about seven thousand objects.

Painted burial shrouds were made in Egypt in the Greco-Roman period (4th century B.C.– 4th century A.D.). In total, about a hundred burial shrouds and their fragments have been found. The first examples of burial shrouds go back to the first century B.C., but their mass production was carried out in the second-third centuries A.D. The majority of burial shrouds come from the ancient necropoleis of Memphis (Sakkara), Thebes, and Faiyum. These linen shrouds were decorated using a unique technique of tempera and glue painting. The shrouds had a ritual purpose of covering or wrapping the mummy swaddled in bandages. However, the perfect state of preservation of some examples, including another shroud from the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts raises the question about their possible use as a kind of "painting" hanging on the walls.

In all of them the deceased are depicted either as mummies or dressed in Roman clothing (chitons or togas), standing alone or accompanied by Anubis and Osiris, the two main gods of the Egyptian pantheon. The faces of the dead were usually painted in portrait style using encaustic tempera (painting with wax-based colours and tempera). The portraits were likely painted while the people were still alive, and then glued onto the shroud. There are six burial shrouds with the third type iconography in the world, including one in the Louvre, three in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin, and two in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. Presumably, they all came from the necropolis of Saqqara and date back to the second century A.D.

Iconography

The Moscow shroud, exhibited in Hall No. 6, shows a unique iconography, representing a woman holding a child by the hand. It has been suggested that the child was a girl, but it is difficult to judge only on the basis of facial features. The child is dressed in a white toga with black stripes (clavi); the hairstyle that is showing the so-called "lock of youth" (a lock of hair above the right ear) was typical for boys. Thus, the person depicted was likely a boy. The young woman is dressed in a long pink tunic with dark purple clavi marking her high social status. She is wearing a white cloak on top of the tunic. In the same hand she's holding the child with, there is a small handbag of pinkish-yellow colour. In the other one she's clutching a branch of myrtle.

The faces of the woman and her son are depicted in portrait style. Unfortunately, the paint on the face of the young woman is severely damaged, but the surviving fragments show that she has an elongated face with almond-shaped black eyes. Black, smoothly combed hair is parted in the middle. Exactly this type of female hairstyle with a typical triangular outline on the forehead makes it possible to date the shroud to the reign of the Emperors Trajan and Hadrian ca. 120–130 A.D.

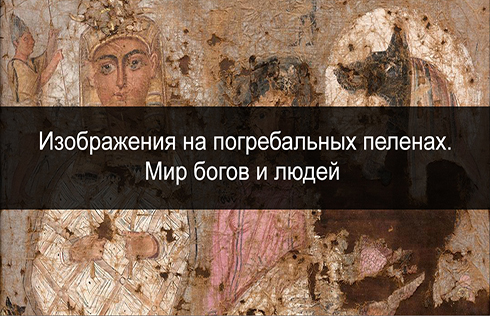

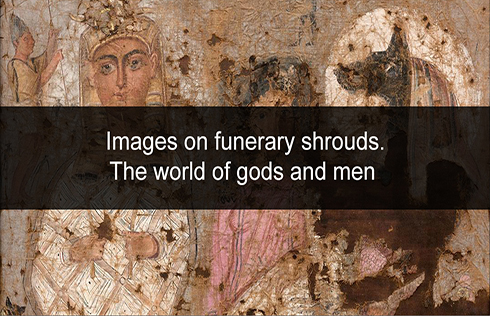

Other than the shroud from the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, such double portraits do not occur on any of the known burial shrouds. It is likely that the mother and son died at the same time and therefore were depicted together on the shroud. It is also possible that only the woman died, and the artist added a representation of a child next to her to indicate her motherhood. The mother and son are accompanied by Anubis, the god of embalming and the guide to the kingdom of the dead, represented as a human with the head of the jackal, and Osiris, the king of the afterworld. The body of Anubis is painted in black, symbolizing the underworld and the eternal life. On his head Anubis is wearing a nemes headcloth, with orange and purple stripes. A white disk of the sun can be seen behind his head. The god is clothed in a long garment imitating a bird's plumage; a decorative checkered band is represented at the lower hem of his garment.

With a gesture Anubis is sending the woman towards Osiris. Osiris has a rounded face with pink cheeks, heavy features, and fleshy lips. Big, greenish, protuberant eyes are accentuated by thick black eyebrows. Osiris is wearing a yellow nemes headcloth, and a horned headdress, which goes back to the Ancient Egyptian Atef crown. In his hands he is holding a crook and a flail, the most ancient symbols of royal power. The mummy of the god is wrapped in pink and white bandages which are placed into a volumetric diamond-shaped pattern, typical for the Roman period. The figure of Osiris on the shroud can be understood in two ways – as a representation of the king of the other world meeting the deceased, and as the representation of the deceased (in our case, the woman), who has risen and has been transformed into Osiris.

The Egyptians believed that after the proper performance of the burial ritual (mummification), the human body acquired a completely different nature and became "enlightened" and transfigured. According to the Ancient Egyptian myth, Osiris was killed by his brother Seth and then was revived by his wife Isis. Thus, each mummified person would become similar to Osiris and could be reborn in the other world. The burial shroud represents the moment when the deceased passes over from the earthly life to the afterlife, and that is why all protagonists are standing in the burial boat which is moving to the west, to the kingdom of Osiris. Solar disks on the boat and behind the head of Anubis also symbolize rebirth after death, likening the dead to the sun that sets in the west and is reborn in the east every day.

The figure of a servant dressed in a yellow tunic with a blue conical hat, lifting water from the well with a special shaduf device, can be seen behind the figure of Osiris. According to the Ancient Egyptian beliefs, the god Osiris gave the dead pure cool water that revived them. Other figures can also be seen on the shroud. These figures were borrowed by the artist from the decoration of Ancient Egyptian tombs and are in one way or another related to the subject of death, the afterlife judgment, and resurrection. They include a deity above the head of the woman, four sons of Horus or canopic jars flanking Osiris and Anubis, and small black stylized figures, probably the spirits of the dead who are welcoming the newly arrived woman in the kingdom of the dead.

Despite the poor state of preservation, it is clear that the shroud was made by an outstanding artist. This is indicated by the high artistic quality of the representations, and skillful combination of pictorial and iconographic methods derived from both Ancient Egyptian and Greco-Roman traditions. Without any doubts, the shroud is a masterpiece of world art.

Conservation

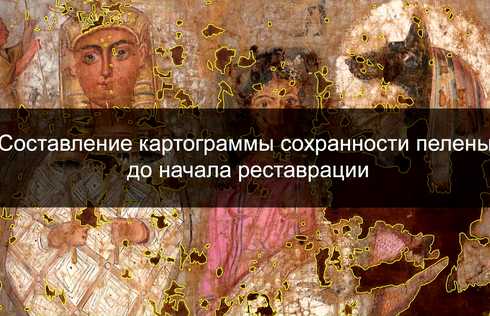

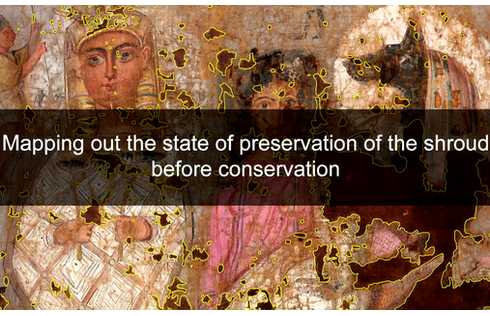

The shroud is in urgent need of conservation. After the transferring to the new canvas, carelessly conducted in the late nineteenth–early twentieth century, numerous fractures and deformations, the loss of canvas, and peeling of paint layers occurred on the shroud with the passage of time. Due to the use of gelatinous glue, the fabric of the shroud degraded and dried up.

In the first phase of conservation works, it is planned to conduct a comprehensive physicochemical and microbiological examination. The results of this examination will help the restorers clarify the conservation procedure and will provide an opportunity to determine which compounds will be ideal for strengthening, cleaning, and conserving the canvas and the paint layer.

In the course of the work it is planned to eliminate ruptures and fractures of the canvas, fragmentarily duplicate the canvas in the places where it disintegrated, clean the surface soiling of the paint, conserve the extant representations, and make a computer reconstruction of the entire painting.

Meticulous and long work needs to be done. It will be unique in bringing together experts from various fields, including restorers of easel tempera, oil painting, and fabric.

It is planned to invite the experts from several research institutions, as well as restorers from the Grabar Art Conservation Center (Moscow), the State Hermitage (St. Petersburg), the Louvre (Paris), and the Metropolitan Museum (New York) to contribute to the project. The experience of world's leading museums will make it possible to develop the most effective methods for the preservation of this unique object.

Go to the Main Website of The Museum

Supported by: